Usman dan Fodio

| Usman dan Fodio عثمان بن فوديُ | |

|---|---|

| 1st Sarkin Musulmi of the Sokoto Caliphate | |

| Reign | 1803–1817 |

| Coronation | Gudu, June 1803 |

| Predecessor | Position established |

| Successor | Muhammad Bello |

| Born | 15 December 1754 Maratta, Gobir |

| Died | 20 April 1817 (aged 62) Sokoto |

| Burial | Hubbare, Sokoto[1] |

| Wives |

|

| Issue | 23 children, including: Muhammad Bello Nana Asmau Abu Bakr Atiku |

| Hausa (Ajami) | عُثْمَانْ طَࢽْ ࢻُودِیُواْ |

| Hausa (Latin) | Usman Ɗan fodiyo |

| Dynasty | Sokoto Caliphate |

| Father | Mallam Muhammadu Fodio |

| Mother | Hauwa bnt Muhammad |

| Personal | |

| Religion | Islam |

| Denomination | Sufism |

| Jurisprudence | Maliki |

| Creed | Ash'ari |

| Tariqa | Qadiri[2][3] |

Shehu Usman dan Fodio (Arabic: عثمان بن فودي, romanized: ʿUthmān ibn Fodio; fullname; 15 December 1754 – 20 April 1817)[4] ( Uthman ibn Muhammad ibn Uthman ibn Saalih ibn Haarun ibn Muhammad Ghurdu ibn Muhammad Jubba ibn Muhammad Sambo ibn Maysiran ibn Ayyub ibn Buba Baba ibn Musa Jokolli ibn Imam Dambube`[5]) was a Fulani scholar, Islamic religious teacher, poet, revolutionary and a philosopher who founded the Sokoto Caliphate and ruled as its first caliph.[6] After the successful revolution, the "Jama'a" gave him the title Amir al-Mu'minin (commander of the faithful). He rejected the throne and continued calling to Islam.

Born in Gobir, Usman was a descendant of the Torodbe clans of urbanized ethnic Fulani people living in the Hausa Kingdoms since the early 1400s.[7] In early life, Usman became well educated in Islamic studies and soon, he began to preach Sunni Islam throughout Nigeria and Cameroon. He wrote more than a hundred books concerning religion, government, culture and society. He developed a critique of existing African Muslim elites for what he saw as their greed, paganism, violation of the standards of the Sharia.[8]

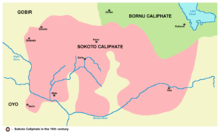

Usman formed and began an Islamic religious and social revolution which spread from Gobir throughout modern Nigeria and Cameroon. This revolution influenced other rebellions across West Africa and beyond. In 1803, he founded the Sokoto Caliphate and his followers pledged allegiance to him as the Commander of the Faithful (Amīr al-Muʾminīn). Usman declared jihad against the tyrannical kings and defeated the kings. Under Usman's leadership, the caliphate expanded into present-day Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Southern Niger and most of Northern Nigeria. Ɗan Fodio declined much of the pomp of rulership, and while developing contacts with religious reformists and jihad leaders across Africa, he soon passed actual leadership of the Sokoto state to his son, Muhammed Bello.[9]

He encouraged literacy and scholarship, for women as well as men, and several of his daughters emerged as scholars and writers.[10] His writings and sayings continue to be much quoted today, and are often affectionately referred to as Shehu in Nigeria. Some followers consider ɗan Fodio to have been a mujaddid, a divinely sent "reformer of Islam".[11] Shehu ɗan Fodio's uprising was a major episode of a movement described as the jihad in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries.[12] It followed the jihads successfully waged in Futa Bundu, Futa Tooro and Fouta Djallon between 1650 and 1750, which led to the creation of those three Islamic states. In his turn, the Shehu inspired a number of later West African jihads, including those of Seku Amadu, founder of the Massina Empire and Omar Saidou Tall, founder of the Toucouleur Empire, who married one of ɗan Fodio's granddaughters.

Early life[edit]

Lineage and childhood[edit]

Usman Danfodio belong to the generation of wandering scholars who started settling in Hausaland since the 1300-1400s, some 400–500 years before the Jihad [13][14] The Sheikh's ancestors were Toronkawa who migrated from Futa Tooro in the 1300s under the leadership of Musa Jokollo. Musa Jokollo is the 11th grandfather of the Shehu. There were 11 generations between Musa Jokollo and Shehu Danfodio.

Abdullahi dan Fodio stated that the Torankawa (Turubbi/Torobe) have Arab ancestry through one Uqba who married a Fulani woman called Bajjumangbu. Muhammed Bello was not sure if it was Uqba ibn Nafi, Uqba ibn Yasir or Uqba ibn Amir.[15][16] Usman dan Fodio's mother Hauwa is believed to be a direct descendant of Muhammad as she was descended from Maulay Idris I, the first Emir of Morocco, who was the great-grandchild of Hasan, grandson of Muhammad.[5] Ahmadu Bello, the first Premier of Northern Nigeria and great-grandson of Muhammed Bello, also said this in his autobiography, tracing his family's connection to Muhammad through Hauwa and Muhammad Fodio.[17]

The Toronkawa first settled in a village called Konni on the borders of Bornu Empire and Songhai Empire, till persecution drove them to Maratta under the leadership of Muhammad Sa'ad, the Sheikh's great-grandfather. A faction of them splitted and moved to Qoloba. It was in Maratta that Usman Danfodio was born on 15 December 1754. He was born as bi Fodiye, dan Fodio or Ibn Fudiyi, 'the son of Fodiye', his father has earned the Fulani title of Fodiye 'the learned'.[18] A further move by the sheikh's father, Muhammad Bn Fodio after 1754 brought them from Maratta to Degel, but several of their relatives still stayed in the town of Konni. Other Toronkawa, such as Gidado's family moved to Kebbi.[18]

His father Muhammad Fodio was an Islamic scholar who the Young Danfodio will later mention in his books as having great influence on him. Muhammad Fodio died in Degel and is buried there.[18] Usman's mother is Hauwa Bn Muhammad. She is believed to be a direct descendant of the Islamic prophet Muhammad as she was descended from Maulay Idris I, the first Emir of Morocco.[19][20] Usman and Abdullahi's first teacher was their mother Hauwa who came from a long line of famous literary scholars. Her mother, Usman's grandmother, was Ruqayyah bin Alim, who was a well respected ascetic and teacher. According to Murray Last, Ruqayya is linked to the branch of the family noted for its learning. Ruqayyah's work Alkarim Yaqbal was popular among Islamic scholars of the 18th and 19th century. Hauwa's father and Ruqayyah's husband, Muhammad bin Uthman bin Hamm, was even more famous and respected than Ruqayya. He was regarded as the most learned Fulani cleric of the time.[21]

Education[edit]

While Usman was young, he and his family shifted to Degel where he studied the Quran.[22] After studying the Qur'an with his father, Danfodio moved to other teachers. They included his relations, Uthman Bn Duri, and Muhammad Sambo.[18] . After being thought by Uthman Binduri, Danfodio joined Jibril bin Umar. Ibn Umar was a powerful intellectual and religious leader at the time, who was a staunch proponent of Jihad. Jibrin Ibn Umar was a controversial figure who later fall out with Danfodio; his preaching on defining who a Muslim is became a subject of disagreement between him and Shehu later in life. The Son of Ibn Umar later joined Shehu at the beginning of the Jihad.[18]. Other students of Ibn Umar include Danfodio's brother Abdullahi dan Fodio, and cousins Muhammad Firabri and Mustapha Bin Uthman[18] At age 20, Usman set up his school in Degel, he was preaching and studying at the same time. Soon after, he became well educated in classical Islamic science, philosophy and theology, and also became a revered religious thinker.

in 1786, Danfodio attended the assembly of his cousin Muhammad bn Raji where he received further academic certifications (p.7)[18].

By 1987, Danfodio was writing a number of books in Arabic and composing long poems in Fulfulde. One of the famous of his books "Ihyā’ al-sunna wa ikhmād al-bid’a (The revival of the Prophetic practice and obliteration of false innovation)" finished before 1973 and seems to established Danfodio's reputaion among contemporary scholars[18]. In his dispute with local scholars over scholasticism, he wrote over 50 works against the quibbles of local scholars.

Call to Islam[edit]

In 1774, Usman began his itinerant preaching as an Mallam and continued preaching for twelve years in Gobir and Kebbi, followed by further five years in Zamfara. Among Usman's well-known students include his younger brother Abdullah, the Hausa King Yunfa, and many others.[22].

His preaching tours took him from to Faru. After his return from Faru, he continue to tour going eyond Kebbi as far as Illo across the Niger River, and in the South travelling to Zugu beyond the Zamfara River valley.

Usman criticized the ruling elite with his writings, condemning them for enslavement, worshiping idols, sacrificial rituals, overtaxation, arbitrary rule and greed.[23] He also insisted on the observance of the Maliki fiqh in personal observances as well as in commercial and criminal law. Usman also denounced the mixing of men and women, pagan customs, dancing at bridal feasts, and inheritance practices against women contrary to Sharia.[24] Soon, the young Danfodio got massive followership among the peasants and other lower class.[18]

Usman broke from the royal court and used his influence to secure approval for creating a religious community in his hometown of Degel that would, he hoped, be a model town. He stayed there for 20 years, writing, teaching and preaching. As in other Islamic societies, the autonomy of Muslim communities under ulama leadership made it possible to resist the state and the state version of Islam in the name of sharia and the ideal caliphate.[14]

He was also influenced by the mushahada or mystical visions he was having. In 1789, a vision led him to believe he had the power to work miracles, and to teach his own mystical wird, or litany. His litanies are still widely practiced and distributed in the Islamic world.[25] In the 1790s, Usman later had visions of Abdul Qadir Gilani, (the founder of the Qadiri tariqah) and ascension to heaven, where he was initiated into the Qadiriyya and the spiritual lineage of Muhammad. Usman later became head of his Qadiriyya brotherhood calling for the purification of Islamic practices.[23] His theological writings dealt with concepts of the mujaddid (renewer) and the role of the Ulama in teaching history, and other works in Arabic and the Fula language.[14]

Notable works[edit]

Danfodio wrote more than a hundred books concerning Economy, History, Law, Administration, Women's rights, government, culture,Politics and society. He wrote 118 poems in Arabic, Fulfulde, and Hausa languages[26].

Balogun (1981, PP. 43-48) has compiled a list of 115 works through various sources [27].Notable among his works include; [28]

- Usul al-`Adl (Principles of Justice)

- Bayan Wujub al-hijrah `ala’l-`ibad7 (description of the obligation of migration for People).

- Nur al-Ibad (Light of the Slaves)

- Najm al-Ikhwan (Star of the Brothers)

- Siraj al-Ikhwan (Lamp for the Brothers)

- Ihyā’ al-sunna wa ikhmād al-bid’a (The revival of the Prophetic practice and obliteration of false innovation)

- Kitab al-Farq (Book of the Difference)

- . Bayan Bid`ah al-Shaytaniyah (Description of the Satanic innovations)

- Abd Al-Qādir b. Mustafā (ten questions put into verse by ‘Uthmanb. Fūdī in one of his non-Arabic poems.)

- Ādāb al-‘ādāt

- Ādāb al-ākhira

- ‘Adad al-dā’i ilā al-dīn

- Akhlāq al-mustafā

- Al-abyāt ‘alā ‘Abd al-Qādir al-Jīlānī

- Al-ādāb.

- Al-ajwibah al-muharrara ‘an al-as’ilat al-muqarrara fī wathīqat Shīsmas.

- ‘Alāmāt almuttabi‘in li sunna rasūl Allāh min al-rijāl wa-al-nisā’

- Al-amr bi-al-ma’rūf wa-al-nahy an al-munkar (enjoining the good and forbidding the evil)

- Al-amr bi-muwālāt al-mu’minīn wa-al-nahy ‘an muwālāt al-kāfirīn.

- . Al- ‘aql al-awwal.

- Al-dālī li-Shaikh ‘Uthmān.

- Al-farq baina ‘ilm usūl al-dīn wa baina ‘ilm al-kalām.

- Al-farq baina wilāyāt ahl al-kufr fi wilāyātihim wa-baina wilāyāt hl al-islam fī wilāyātihim

- Al-fasl al-awwal

- Al-hamzīyah

- Al-jāmi’.

- Al-jihād

- Al-khabar al-hādī ilā umūr al-imām al-mahdī

Reforms[edit]

Women Right[edit]

The first major revolutionary action that Danfodio took at the beginning of his mission was the mass education of women. The Shehu criticized ulama for neglecting half of human beings and ‘leaving them abandoned like beasts’ (Nur al-Albab, p. 10, quoted by Shagari & Boyd, 1978, p. 39). He responded convincingly to objections raised against this (ibid. pp. 84-90) raised by Elkanemi of Borno

He equally educated and taught his sons and his daughters who carried on his mission after him. Several of his daughters emerged as scholars and writers.8 Especially his daughter Nana Asma’u translated some of her father’s work into local languages. The Shehu criticized ulama for neglecting half of human beings and ‘leaving them abandoned like beasts’ (Nur al-Albab, p. 10, quoted by Shagari & Boyd, 1978, p. 39)[29]

The first major revolutionary action that Danfodio took at the beginning of his mission was the mass education of women. It was particularly revolutionary because Danfodio decided that women were to receive the exact kind of education as men and thus he placed them in the same classrooms[30].He encouraged literacy and scholarship, for women as well as men, and several of his daughters emerged as scholars and writers.[10]. For popularization of knowledge he authored wathiqat al-Ikhwan.

Economic Reforms[edit]

The Shehu strongly criticized the Hausa ruling elite for their heavy taxation and violation of the Muslim Law. He ‘condemned oppression, all unfairness, the giving and acceptance of bribes, the imposition of unfair taxes, the seizing of land by force, unauthorized grazing of other people’s crops, extraction of money from the poor, imprisonment on false charges and all other injustices (Shagari and Boyd, 1978, p. 15) .The Shehu’s followers were required not to remain idle. They were encouraged to learn a craft in order to earn a living. It was considered improper to eat what one had not earned by one’s own efforts’10. They engaged in various handcrafts to produce necessities of life (Shagari and Boyd, 1978,. p. 18).

He argued for revival of just Islamic economic institutions such as al-hisbah, hima, bayt al-mal (State treasury), Zakat, Waqf, etc. Mostly his economic ideas are found in his work Bayan Wujub al-Hijrah `ala’-Ibad. Other works in which some economic ideas are found are Kitab al-Farq, Siraj al-Ikhwan, Bayan Bid`ah al-Shaytaniyah, Najm al-Ikhwan and Nur al-Ibad[31].

Economic Role of the State[edit]

On the economic role of the state, the Shehu considers the state responsible for the betterment of people’s mundane and religious life. The government should remove obstacles lying in their way of progress. That the people enjoy peace and prosperity is more ensuring for the security of the country and strength of the government than maintaining huge army (Dan Fodio, 1978, pp. 65-66). From this Gusau infers that ‘the Shehu saw the government as a guarantor of minimum livelihood for all subjects in need of such assistance. Also the government was to ensure the provision of public utilities such as roads, bridges, mosques, City walls that ensure comfort and a life of piety for the citizens’ (Gusau, 1989, p. 143)[32].

Public Finance[edit]

On Public finance, The Shehu considers the rule of rightly guided caliphs (al-khulafa al-Rashidun) as a true model for any government. Based on this he prescribes that the rulers should take only the ordinary man’s share as their salary from the public treasury and live a simple life (ibid, p. 150). He considers the public treasury in the hand of the ruler as property of an orphan in the hand of a caretaker. This is perhaps with reference to a verse in the Qur'an (4:6) which says that "If the guardian [of an orphan] is well-off, let him claim no remuneration. But if he is poor, let him have for himself what is just and reasonable". Thus, if the rulers have sufficient means to satisfy their basic needs, they should not take any thing from the treasury (Gusau, 1989, p. 150)[32]. Shehu forbade revenue officers to accept gifts from the subjects (ibid).

The Shehu enumerated the sources of income for the Islamic state. They include one fifth of the spoil of war (al-khumus), land tax (kharaj), poll tax (jizyah), booty (fay = enemy’s property obtained without actual combat), tithe (ushr), heirless property and lost found whose owner is not traceable (Dan Fodio, 1978, p. 123). Zakat, with its specified beneficiaries formed a separate category, distinguished from the other sources of public revenue. In his book Usul al-Adl (The basis of Justice) he also mentions the custom duties (ushur) as a source of public revenue.

Economic System[edit]

The Shehu advocates foundation of an economic system based on values such as justice, sincerity, moderation, modesty, honesty, etc. According to him justice is the key for progress while injustice leads to decadence. A just government can last even with unbelief but it cannot endure with injustice(Dan Fodio, 1978, p. 142). On the other hand he warned against the unhealthy practices such as fraud, adulteration and extravagance and their bad consequences in the economy (Dan Fodio, 1978, p. 142). He exalted labour and hard work, and rejected begging. He encouraged his follower to engage in earning livelihood even through an ordinary occupation (Kani, 1984, pp. 86-87). Division of labour and cooperation occupy a very high place in his economic thought (Balogun, 1985, p. 30, quoted by Sule Ahmed Gusau, 1989)[32]. Property earned through fraudulent means would be confiscated and the funds obtained credited to the state treasury.

The Shehu was very emphatic on Fair market functioning. In his work Bayan al-Bid`ah al-Shaytaniyah (On Satanic Innovations) he forbade ignorant persons from dealing in market. It is for the sake of fairness in dealing in the market that he emphasized revival of the Hisba institutions whose functions include checking the prices, Inspection of the quality of goods,correct weights and measures, prevention of Fraud and Usurious practices, removal of Monopolisation of products, etc. (The Shehu’s work al-Bid`ah al-Shaytaniyah, quoted by Kani, p. 65)[33].

Public Expenditure[edit]

On public expenditure, the Shehu based his ideas on Ibn al-Juza’iy (d.741/1340) and al-Ghazali (d. 505-1111). In his treatise to the Emirs, Shehu emphasised expenditure on Defence by preparing armaments and by paying soldiers. If there remains anything, it goes to the judges, state officials, for the building of mosques and bridges and then it is divided among the poor. If any still remains, the Emir has the option of either giving it to the rich or keeping it (in the bayt al-mal) to deal with disasters that may occur (ibid. p. 131, quoted by Gusau, 1989, pp. 144-45)[32].

In his Usul al-`Adl which is summary of a work of Al-ghazali, the Shehu mentions heads of expenditure of bayt al-mal as fortification of Muslim cities, teachers’ salaries, judges’ salaries, mu’azzins’ salaries, all those who work for Islam and the poor. “If anything in left after all these heads, the surplus is to be kept in the treasury for the emergencies. The fund may also be used for building mosques, free Muslim captives, freeing debtors, and can be used for helping those without means to marry or those without means to go for hajj, etc. (Gusau, 1989, p. 151). The Shehu reiterated that the revenue gotten through Zakat will be spent as prescribed in the Qur’an. It will be spent in the same region from where it is collected, as ordained in the hadith. According to the Shehu, the zakat al-fitr (poor due at the fast breaking) would be spent on the poor and the needy only. The state's income is not exclusively for the poor. Nor is it necessary to spend equally on all heads of expenditure (Gusau, 1989, pp. 144-145).

Land Reforms[edit]

In this regard, the Shehu divides lands into two categories ma`mur (useable and inhabited) and mawat (dead land, uninhabited and uncultivated). Depending on whether such lands were captured by force, by peace treaty or their owner embraced Islam, they have different rules for distribution, allocation, grants, endowment, or enclosure (hima) (Gusau, 1989, pp. 145-46). All lands belong to the state. The Shehu declared all lands as Waqf, or owned by the entire community. However, the Sultan allocated land to individuals or families, as could an emir. Such land could be inherited by family members but could not be sold.Tax on land was introduced.

Background to the Jihad[edit]

Origins and foundation[edit]

In 1780–the 1790s, Usman's reputation increased as he appealed to justice and morality and rallied the outcasts of Hausa society.[22] The Hausa peasants, slaves and preachers supported Usman, as well as the Toureg, Fulbe and Fulani pastoralists who are overtaxed and their cattle seized by powerful government officials.[18] These pastoralist communities were led by the clerics living in rural communities who were Fulfulde speakers and closely connected to the pastoralists. Many of Usman's followers later hold the most important offices of the new states. Usman's jihad served to integrate several peoples into a single religious-political movement.[34] The sultan responded violently to Danfodio's Islamic Community. Some members of the Jama'a were imprisoned.[18]

In the Shaykh’s book, “Tanbih al-ikhwan”, we get his brother’s account of why the Jihad began. This was narrated by Abdullah at the insistence of the Shaykh himself

The king of Gobir then started provoking some of the Shaykhs followers and terrorized them. He dispatched a campaign against them, and in a particular instance, his troops captured some of our men, including their wives and children and started selling them as slaves before our eyes. We were even threatened that the same fate might befall us ourselves.

Eventually, the Sarkin Gobir sent a message to Shehu ordering him to take his family away and leave his town but that he must not take along with him any of his followers.Thereupon the Shaykh replied;

" I will not part with my people, but I am prepared to leave along with all those who wish to follow me. Those who choose to stay can of course do so’. We made our Hijra from their midst on that Thursday in the year 1218 (1804). On the 12th of Zulki’da we reached the wilderness of the frontier. Muslims kept on making their own Hijra to join us. Sarkin Gobir instructed those in authority under him to seize the possessions of those making Hijra and to prevent their people coming to join us…”

— Abdullahi bin Fodio, Tanbih Al-Ikhwan

By the year 1788–89, The authority of Gobir began declining, as the power of the Shehu is increasing. Feeling threatened the 75-year old ailing Sultan of Gobir, Bawa Jan Gwarzo summoned Shehu at Magami during Eid al-Adha.[18] All the scholars of the royal court joined Danfodio's followers leaving the Sultan. Danfodio managed to win the famous 5 concessions. These are what Danfodio demanded;[18]

- That all prisoners be free

- That anyman wearing the Turban (A symbol of Shehu's Islamic Community - The Jama'a) be respected.

- To be allowed to call to God

- And none should be stopped from responding to the call.

- That his subjects should not be burdened with tax.

Conflict with Nafata[edit]

After Bawa's death, the power of Gobir continue to decline due to battles with the neighbouring states. Yaaqub son of Bawa was killed in a battle, hostility between Gobir and Zamfara crystallised.[18] In Zurmi,Ali Al-faris , the leader of the Alibawa Clan of Fulani was killed by the Gobirawa, the Alibawa will later join hands with the Shehu. The Zamafarawa too, who were recently subdued by the Gobirawa were again in revolt and Nafata lacked the power to put the revolt down. At home, the Shehu is getting massive followership at the expense of the Sultan.[18]

In 1797–98, King Nafata of Gobir in trying to quel the power of the Shehu decided to delegalise some Islamic practices. He forbade Shaykhs to preach, the Islamic community from wearing turbans and veils (Hijab), prohibited conversions and ordered converts to Islam to return to their old religion.[22][34] The proclamation thus reversed the policy of the Sultan of Gobir Bawa made ten years earlier.[18] This was highly resented by Usman who wrote in his book Tanbih al-Ikhwan 'ala away al-Sudan ("Concerning the Government of Our Country and Neighboring Countries in Sudan") Usman wrote: "The government of a country is the government of its king without question. If the king is a Muslim, his land is Muslim; if he is an unbeliever, his land is a land of unbelievers. In these circumstances, anyone must leave it for another country".[35]

Assassination attempt[edit]

In 1802, Nafata's successor Yunfa, a former student of Usman, turned against him, revoking Degel's autonomy and attempting to assassinate Usman at Alkalawa. He captured some of Shehus followers as prisoners.[36] After unsuccessful attempt, Yunfa then turned for aid to the other leaders of the Hausa states, warning them that Usman could trigger a widespread jihad.,[37]

Yunfa at the end of his first year faced rebellion from Zamfara, Invasion by Katsina, the Sullubawa who are loyal to Katsina, and the Muslim Community who are becoming increasingly powerful and who are restive unde the moderation of the Shehu.[13]

The crisis precipitated as a Gobir expedition returning to Alkalawa with Muslim prisoners was made to free them as it went up past Degel where the Muslim community is concentrated. Yunfa though not in the command of the expedition, could not overlook the challenge. Yunfa's response was an attempt to kill the Sheikh [18]. Yunfa's forces attacked Gimbana and muslims were taken as prisoners.

Exile/Emigration/Hijra[edit]

It is at this point that Danfodio wrote the book Masa'il muhimma where he stated the Obligation of emigration on persecuted Muslims.[18] With the threat of attack from Gobir, the Muslim community had to reach out of Yunfa's army. Though they were not prepared, they fled to Gudu, a journey of about four or five days, and a distance of about sixty miles [18]. Not everybody could make the journey, the Tuareg scholar, Agali who is carrying Shehu's books on top of camels and donkeys had to return to with camels to help in evacuation.

After they fled Degel, other Muslim communities across Hausaland began to join the migrating entourage of Danfodio. Muhammed Bello, went to Kebbi and other neighbouring states distributing Pamphlets calling Muslims out for the emigration (Hijrah). It is in this period that the book Wathiqat ahl-Sudan was circulated (a message to the people of Hausaland) containing brief instructions on what is islamically lawful and unlawful and what causes of action are compulsory for a Muslim as an individual an Muslims as a community.[18] Emigrants continue to join the Shehu for months after the original hijrah, some coming with and without their families and belongings.

The king of Gobir worried about the depopulation of his kingdom tried to stop further emigration by harrassingand confiscating the goods of the refuges but to no avail (p.24)[18]

Notable Companions[edit]

At Degel with the Shehu is hs father, Muhammad Fodiye, his elder brother, Ali and his younger brother, Abdullahi.

Another notable personality is Umar Al-Kammu, his closest friend who accompanied him on the occasion of Yunfa's assasination attempt. He was third after Abdullahi and Muhammed Bello in saluting Shehu as Commander of the Believers. He acted as a treasurer during the Jihad. He was present during the battle of Tsuntsua, but died before the Sheikh in Birnin Fulani near Zauma. His remains were later brought to Sokoto by Bello were he was buried near the Shehu.

The Scribes : In the book Raud Al-jinan,17 scribes were mentioned, notable among them are Al-Mustapha, the Chief scribe. Two are nicknamed Al-Maghribi, implying North African origin and another "Malle" indicating Malian ancestry.

The Imams : Notable among them is Imam Muhammad Sambo who died in the battle of Tsuntsua; Muezzin Ahmad Al-Sudani who died early in Sarma early in the Jihad; Muhammad Shibi; M. Mijji, Yero , etc.

Sulaiman Wodi: Sent with a letter to the Sarkin Gobir at the start of the Jihad. Later acted as a treasurer.

62 neighbours. When the Muslims went to Alkalawa to meet Bawa, there are said to be more than a thousand scholars with the Sheikh[18]. At Tsuntsua, Bello said 2,000 died, 200 of them being memorisers of the Holy Qu-ran.

Outside the circle of the Sheikh, 69 other scholars were mentioned in Raud Al-jinan, a third of them are likely Fulani or have Fulani names suggesting a Fulani origin.

On ethnic composition, Murray Last citing the book Rawd al-jinan, apart from the Shehus close community from Degel, 69 other scholars were mentioned, roughly a third are Fulani or have Fulani names which suggest Fulani origin, "but the rationale of the list is not evident:most of the first thirty-four are identifiably connected with the Sokoto area, while 15 of the rest are identifiably unconnected"[18]

Declaration of Jihad[edit]

Emergence as the Commander of the Believers.[edit]

With negotiations between the Muslim Community and Gobir in a stalemate, an attack is therefore imminent, the Muslims prepared defences and elected a leader. Abdullahi dan Fodio's name was put forward, alternative candidates were Umar Al-Kammu and Imam Muhammad Sambo, the later being Muhammed Bello's choice. Usman's followers entitled him the Commander of the Believers (Amīr al-Muʾminīn) and elected him as the leader. They also gave the title Sarkin Muslim (Head of Muslims) to Usman.[38] . The salute of allegiance was fisrt given by Abdullahi dan Fodio, and then by Muhammed Bello. Danfodio was old (50 years) and weak and was to take no part in the fighting. The position was mere ceremonial (p. 24) [18].

By April in the same year, the Muslim Community have mobilised in Gudu and were ready to face the emerging cavalry of Gobir. The call for Jihad have spread widely across Hausaland and even beyond as can be seen in this poem written by a Bornu scholar;

Verily, a cloud has settled on God's earth

A cloud so densed that escape from it is impossible

Everywhere from Kordofan and Gobir

And the cities of the Kindin (Tuaregs)

Are settlements of the dogs of Fellata (Bi la'ila)

Serving God in their dwelling places

(I swear by the life of the Prophet and his overwhelming grace)

In reforming all districts and provinces

Ready for future bliss

So in this year of 1214 they are following their beneficient theories

As though it were time to set the world in order by preaching

Alas! that I know all about the tongue of the fox.— Borno Scholar, in

In the same year, Usman started the jihad and founded the Sokoto Caliphate.[39] By this time, Usman had assembled a wide following among the Fulani, Hausa peasants and Toureg nomads.[23] This made him a political as well as religious leader, giving him the authority to declare and pursue a jihad, raise an army and become its commander. There were widespread uprisings in Hausaland and its leadership was largely composed of the Fulani and widely supported by the Hausa peasantry, who felt over-taxed and oppressed by their rulers.[40]

After Usman declared Jihad, he gathered an army of Hausa warriors to attack Yunfa's forces in Tsuntua. Yunfa's army, composed of Hausa warriors and Tuareg allies, defeated Usman's forces and killed about 2,000 soldiers, 200 of whom were hafiz (memorizers of the Quran). Yunfa's victory was short-lived as soon after, Usman captured Kebbi and Gwandu in the following year.[41] At the time of the war, Fulani communications were carried along trade routes and rivers draining into the Niger-Benue valley, as well as the delta and the lagoons. The call for jihad reached not only other Hausa states such as Kano, Daura, Katsina and Zaria, but also Borno, Gombe, Adamawa and Nupe.[42] These were all places with major or minor groups of Fulani alims.[citation needed]

The Battle of Tabkin Kwotto[edit]

The first skirmishes when a small group of soldiers from Gobir were beaten back (p.24)[13]. The Muslims went to capture Matankari and Konni, both important towns on their northern flank. The division of the Booty was not in accordance with Islamic law and for this reason, the Shehu appointed Umar Al-Kammu to serve as a treasure.

The Muslim Community were warned of the approching cavalry of Yunfa first by a Toureg nomad and secondly by some Fulani soldiers of Yunfa who escaped the cavalry. Yunfa first approached the Sullubawa for alliance before heading on.

On the strength of the Cavalry, Muhammed Bello said its a hundred cavalry strong consisting of mostly Tuaregs, Sullubawa and Gobirawa while Danfodio's army consist of Hausa, Fulani, Konni Fulani who provide local support, Tuaregs under the leadership of Agali and Adar muslims including the son of Emir of Adar who also joined the Hijra (p. 27)[18].

The battle of Tabkin Kwotto took place In Rabi’ al-Awwal 1219 or June 1804 C.E., the heavily armed Gobir forces under Yunfa met the ill-equipped and smaller army of the Jama’a under the commendarship of Abdullah. Though the muslims are smaller, ill-equiped with only a few horses and bows, they were helped by geographical factors. On one flank, they are covered by a river which now had water due to rainy season. The ground though flat is covered in thick forest as well. The advantage in morale was also high; facing destruction if they are captured.

By the lake Kwotto near Gurdam, not far from Gudu. Soon after the battle broke out, the Muslims were able to defeat the Gobir forces, who were then forced to flee. Abdullah describes how he shadowed the Gobir army for days, trying to bring it to battle, yet they were reluctant to meet him on a battleground of his choosing. With a plan to get behind him and cut his line of retreat, the Gobir army moved west to of his army and took up a position near Lake Kwotto (Tabkin Kwotto in Hausa), on hillyground with a cover of thicket in their front, which they were counting on to keep the Muslims at bay. Beyond the thicket laid an open ground which the cavalry needed to ride down the Muslims. They then waited there for the night, expecting an easy win against the Muslims the next day. Abdullah who had figured out the plan and had confidence in his army’s mobility and good shooting prowess of his archers, decided to fight them at the lake. Here, the Muslim army piously performed prayers, promising themselves to death or victory in the bloody battle area.

The battle began around midday with a leading assault from Abdullah, the battle then quickly evolved into bloody hand-to-hand combat, waged with axes, swords and short ranged archery. By noon, the Gobirawa had had enough, they turned around, hoping to flee. Yunfa himself, quickly fleed away from the field of battle. This battle boosted the moral of the muslim community. Abdullah further wrote letters inviting other muslims to join the victorious holy fighters. With this, the Muslim army received a huge wave of reinforcements from initial by-standers.

Food scarcity[edit]

The rains of 1804 have already started but food supply before the year's harvest were still low. The local villagers were hostile and unwilling to sell Maize to the muslim community. When a source of food is finished the only alternative is to move to a new area. According to Murray Last, The campaigns of the Jihad explicable in these terms; the search for food, in addition pasture and water for the cattles.

After the success at Tabkin Kwotto, some local kings started aligning themselves with the Shehu notable among them were the leaders of Mafara, Burmi and Donko leaving only the Sarki of Gummi in South-Western Zamfara to support Gobir. They knew the Shehu 20 years previously when he was on his preaching tours in Zamfara. They sent traders with food to the Muslim Community, but according to Muhammed Bello, their friendship was due to their hostility with Gobir than there adherence to Islam or the need for reform. (p. 27). Still the issue of food scarcity wasn't solved. The peasentry were losing their patience.

The Battle of Tsuntsua[edit]

With the harvest in October 1804, the first set of the aggresive campaign began, able to retreat out of the valleys into scrubland, they were safe against cavalry attack. They gain more freedom of movement , they therefore move to the hinterland of the Gobir capital, Alkalawa.

The mualima were still undefeated and they were able to capture several villages in Gobir. A mediation attempt by Sarki of Gummi was unsuccessful as the muslims are now strong enough to dictate terms of any agreement. They demanded that the Yunfa come in person to the Sheikh.

The Muslims continued to gain allies. The Gobir army started to attack their Sullubawa alies snce some started to favour the Shehu. On the borders of Adar and Gobir, a group of Muslims under Tuareg Agali have been fighting. In South-eastern Gobir, in the old Zamfara, the muslims had furher allies; the Alibanawa Fulani who had suffered in the hands of Gobir.

It was in the month of Ramadan, With the Muslim's camp now less than a day's journey to the capital, and dispersed in search of food, the Gobir army with their Tuareg allies launched a counterattack at Tsuntsua ,two miles from the capital. According to Muhammed Bello, the muslims lost about 2000 people, 200 of which knew the Qur'an by heart. Muhammed Bello was sick while Abdullahi dan Fodio was wounded in the leg. Among the dead were relatives of Shehu like Imam Muhammad Samo, Zaid bin Muhammad Sa'ad and Mahmud Gurdam.

After the defeat at Tsuntsua, the Muslims stayed the rest of Ramadan in the valley before starting upriver towards Zamfara in January and February in search of food.

Expansion of the Jihad[edit]

The defeat of Gobir alerted many of the Hausa kings and chiefs, and many of them began a strong assault on the Islamic communities in their territories. Meanwhile, a commercial embargo was placed on the town of Gudu and its surroundings. It was here that the ties of the Shehu with Zamfara came into play. Although, it was pointed out that the amity of Zamfara was due to their enmity with Gobir and not born out of adherence to Islam[13].

After the battle of Kwotto, it became evident that the Jihad was now no longer a matter of defense against Gobir, but a matter of saving the cause of Islam, which the Hausa kings were set to destroy. Considering this, the Shaykh appointed fourteen leaders and sent them back to their respective territories and communities, to lead their people in Jihad against their enemies who had assaulted them. It was these developments that led to the major spread of Islam all over Hausa land and even parts of Bornu

By 1808, Usman had defeated the rulers of Gobir, Kano, Katsina and other Hausa Kingdoms.[43] After only a few years, Usman found himself in command of the states. The Sokoto Caliphate had become the largest state south of the Sahara at the time. In 1812, the caliphate's administration was reorganized, with Usman's son Muhammed Bello and brother Abdullahi dan Fodio carrying on the jihad and administering the western and eastern governance respectively.[44] Around this time, Usman returned to teaching and writing about Islam. Usman also worked to establish an efficient government grounded in Islamic law.[45]

The Sokoto Caliphate was a combination of an Islamic state and a modified Hausa monarchy. Muhammed Bello introduced Islamic administration, Muslim judges, market inspectors and prayer leaders were appointed, and an Islamic tax and land system were instituted with revenues on the land considered kharaj and the fees levied on individual subjects called jizya, as in classical Islamic times. The Fulani cattle-herding nomads were sedentarized and converted to sheep and goat raising as part of an effort to bring them under the rule of Muslim law. Mosques and Madrassahs were built to teach the populace, Islam. The state patronized large numbers of religious scholars or mallams. Sufism became widespread. Arabic, Hausa and Fulfulde languages saw a revival of poetry, and Islam was taught in Hausa and Fulfulde.[34]

Death[edit]

In 1815, Usman moved to Sokoto, where Bello built him a house in the western suburbs. Usman died in the same city on 20 April 1817, at the age of 62. After his death, his son Muhammed Bello, succeeded his as amir al-mu'minin and became the second caliph of the Sokoto Caliphate. Usman's brother Abdullahi was given the title Emir of Gwandu and was placed in charge of the Western Emirates of Nupe. Thus, all Hausa states, parts of Nupe and Fulani outposts in Bauchi and Adamawa were all ruled by a single political-religious system. By 1830, the jihad had engulfed most of what are now Northern-Nigeria and the northern Cameroon. From the time of Usman ɗan Fodio to the British conquest at the beginning of the 20th-century there were twelve caliphs.[19]

Legacy[edit]

Usman has been viewed as the most important reforming leader of Africa.[22] Muslims view him as a Mujaddid (renewer of the faith).[11] Many of the people led by Usman ɗan Fodio were unhappy that the rulers of the Hausa states were mingling Islam with aspects of the traditional regional religion. Usman created a theocratic state with a stricter interpretation of Islam. In Tanbih al-ikhwan 'ala ahwal al-Sudan, he wrote: "As for the sultans, they are undoubtedly unbelievers, even though they may profess the religion of Islam, because they practice polytheistic rituals and turn people away from the path of God and raise the flag of a worldly kingdom above the banner of Islam. All this is unbelief according to the consensus of opinions".[46] In Islam outside the Arab World, David Westerlund wrote: "The jihad resulted in a federal theocratic state, with extensive autonomy for emirates, recognizing the spiritual authority of the caliph or the sultan of Sokoto".[47] Usman addressed in his books what he saw as the flaws and demerits of the African non-Muslim or nominally Muslim rulers. Some of the accusations he made were corruption at various levels of the administration and neglect of the rights of ordinary people. Usman also criticized heavy taxation and obstruction of the business and trade of the Hausa states by the legal system. Dan Fodio believed in a state without written constitution, which was based on the Quran, the Sunnah and the ijma.[31]

Personal life[edit]

Usman ɗan Fodio was described as well over six feet (1.8 m), lean and looked like his mother Sayda Hauwa. His brother Abdullahi dan Fodio (1761–1829) was also over six feet (1.83 m) in height and was described as looking more like their father Muhammad Fodio, with darker skin and a portly physique later in life.[citation needed]

In Rawd al-Janaan (The Meadows of Paradise), Waziri Gidado ɗan Laima (1777–1851) listed ɗan Fodio's wives as his first cousin Maymuna and Aisha ɗan Muhammad Sa'd. With Maymuna he had 11 children, including Aliyu (1770s–1790s) and the twins Hasan (1793– November 1817) and Nana Asmaʼu (1793–1864). Aisha was also known as Gaabdo ('Joy' in Fulfulde) and as Iyya Garka (Hausa for 'Lady of the House/Compound'). She was famed for her Islamic knowledge and for being the matriarch of the family. She outlived her husband by many decades. Among others, she was the mother of Muhammad Sa'd (1777 – before 1800).[48]

Writings[edit]

Usman ɗan Fodio "wrote hundreds of works on Islamic sciences ranging from creed, Maliki jurisprudence, hadith criticism, poetry and Islamic spirituality", the majority of them being in Arabic.[49] He also penned about 480 poems in Arabic, Fulfulde and Hausa.[50]

See also[edit]

- Hausa Kingdoms

- History of Nigeria

- Legends of Africa

- Makera Assada

- Muhammad al-Maghili

- Muhammed Bello

- Nana Asmaʼu

- Sokoto

- Sokoto Caliphate

- Usmanu Danfodiyo University

References[edit]

- ^ OnlineNigeria.com. SOKOTO STATE, Background Information (2/10/2003).

- ^ University of Pennsylvania African Studies Center: "An Interview on Uthman dan Fodio" by Shireen Ahmed 22 June 1995

- ^ Loimeier, Roman (2011). Islamic Reform and Political Change in Northern Nigeria. Northwestern University Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-8101-2810-1.

- ^ Hunwick, John O. 1995. "Arabic Literature" in Africa: the Writings of Central Sudanic Africa, pp.

- ^ a b Last, Murray. Genealogy of Shaikh Uthman b Fodiye and some Scholars related to him (PDF). Premium Times.

- ^ I. Suleiman, The African Caliphate: The Life, Works and Teachings of Shaykh Usman Dan Fodio (1757–1817) (2009).

- ^ T. A. Osae & S. N. Nwabara (1968). a Short history of WEST AFRICA A.D 1000–1800. Great Britain: Hodder and Stoughton. p. 80. ISBN 0-340-07771-9.

- ^ "Karanta Cikakken Tarihin Shehu Usman Dan Fodio : Abubuwan da Yakamata Ku sani dangane da Rayuwar Mujaddadi Shehu Usman Dan Fodio". Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ "Usman Dan Fodio's Biography". Fulbe History and Heritage. 17 March 2016. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ a b "Usman Dan Fodio, a great reformer". guardian.ng. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ a b John O. Hunwick. "African And Islamic Revival" in Sudanic Africa: A Journal of Historical Sources : #6 (1995).

- ^ "Suret-Canale, Jean. "The Social and Historical Significance of the Fulɓe Hegemonies in the Seventeenth, Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries." In Essays on African History: From the Slave Trade to Neocolonialism. translated from the French by Christopher Hurst. C. Hurst & Co., London., pp. 25–55". Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d Last, Murray. "The Sokoto Caliphate".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c Lapidus, Ira M. A History of Islamic Societies. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2014, p. 469.

- ^ Gwandu, Abubaker Aliu (1977). Abdullahi b. fodio as a Muslim jurist (Doctoral thesis). Durham University.

- ^ Abubakar, Aliyu (2005). The Torankawa Danfodio Family. Kano, Nigeria: Fero Publishers.

- ^ Bello, Ahmadu (1962). My life. Internet Archive. Cambridge [Eng.] : University Press. p. 239.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Last, Murray (3 March 2021), "The Sokoto Caliphate", The Oxford World History of Empire, Oxford University Press, pp. 1082–1110, retrieved 18 April 2024

- ^ a b Last, Murray (1967). The Sokoto Caliphate. Internet Archive. [New York] Humanities Press.

- ^ Last, Murray. Genealogy of Shaikh Uthman b Fodiye and Some Scholars related to him c1800 (PDF). Premium Times.

- ^ Hashimi, A.O. (2020). "Gender Balance and Arabic Cultivation: A Case Study of Selected Female Arabic Cultivators in Pre-Colonial Northern Nigeria" (PDF). Islamic University Multidisciplinary Journal. 7 (2): 132.

- ^ a b c d e "Usman dan Fodio | Fulani leader | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Meredith, Martin (2014). The fortunes of Africa: a 5000-year history of wealth, greed, and endeavor. Internet Archive. New York: Public Affairs. pp. 164–165. ISBN 978-1-61039-459-8.

- ^ "Keywords; history, nation building, Nigeria, role | Government | Politics". Scribd. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ "الدلائل الشيخ عثمان ابن فودي" – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Poems written by Usman dan Fodio (and others)". Endangered Archives Programme. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ Islahi, Abdul. (2008). Shehu Uthman Dan Fodio and his economic ideas.

- ^ Akintola, Ameer. (2023). Shaykh ‘Uthman bn Fodio : A Short History.

- ^ Shagari, Shehu Usman Aliyu; Boyd, Jean (1978). Uthman Dan Fodio: The Theory and Practice of His Leadership. Islamic Publications Bureau.

- ^ "THE WOMEN AROUND DANFODIO". Gainaako. 9 March 2014. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ a b Abdul Azim Islahi (1 January 2008). "Shehu Uthman Dan Fodio and his economic ideas" (pdf). MPRA (Paper N. 40916). Islamic Economics Institute, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah: 7. Archived from the original on 26 January 2013 – via researchgate.net].

- ^ a b c d Gusau, Sule Ahmed, 1989, “Economic Ideas of Shehu Usman Dan Fodio, JIMMA, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 139-151.

- ^ Kani, Muhammad Ahmad (1984), The intellectual origin of Sokoto jihad, Ibadan, Imam Publication.

- ^ a b c Lapidus, pg 470

- ^ Usman dan Fodio: Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^ "Usman Dan Fodio: Progenitor Of The Sokoto Caliphate". The Republican News. 14 October 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ The Islamic Slave Revolts of Bahia, Brazil: A Continuity of the 19th Century Jihaad Movements of Western Sudan?, by Abu Alfa Muhammed Shareef bin Farid, Sankore' Institute of Islamic African Studies, www.sankore.org. Archived 15 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

Also see Lovejoy (2007), below, on this. - ^ "THE EMPIRES AND DYNASTIES – The Muslim Yearbook". 16 July 2019. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ "Fodio, Usuman Dan | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ "Usman dan Fodio | Fulani leader". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ Spencer C. Tucker (2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East [6 volumes]. ABC CLIO. p. 1037. ISBN 978-1-85109-672-5. Retrieved 19 November 2014.

- ^ Ososanya, Tunde (29 March 2018). "Usman Dan Fodio: History, legacy and why he declared jihad". Legit.ng – Nigeria news. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "Usman dan Fodio: Founder of the Sokoto Caliphate | DW | 24 February 2020". DW.COM. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ "Muḥammad Bello | Fulani emir of Sokoto". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ Nigeria, Guardian (12 May 2019). "Usman Dan Fodio, a great reformer". The Guardian Nigeria News - Nigeria and World News. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ "Salaam Knowledge". Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ^ Christopher Steed and David Westerlund. Nigeria in David Westerlund, Ingvar Svanberg (eds). Islam Outside the Arab World. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1999. ISBN 0-312-22691-8

- ^ Ogunnaike, Oludamini (2021). "A Treatise on Practical and Theoretical Sufism in the Sokoto Caliphate" (PDF). Journal of Sufi Studies. 10: 152–173.

- ^ Dawud Walid (15 February 2017), "Uthman Dan Fodio: One of the Shining Stars of West Africa", Al Madina Institute. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- ^ Yahaya, Ibrahim Yaro (1988). "The Development of Hausa Literature. in Yemi Ogunbiyi, ed. Perspectives on Nigerian Literature: 1700 to the Present. Lagos: Guardian Books" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 11 July 2011. Obafemi, Olu. 2010. "50 Years of Nigerian Literature: Prospects and Problems" Keynote Address presented at the Garden City Literary Festival, at Port Harcourt, Nigeria, 8–9 Dec 2010.]

Bibliography[edit]

- F. H. El-Masri, "The life of Uthman b. Foduye before the Jihad", Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria (1963), pp. 435–48.

- Writings of Usman dan Fodio, in The Human Record: Sources of Global History, Fourth Edition/ Volume II: Since 1500, ISBN 978-12858702-43 (page:233-236)

- Asma'u, Nana. Collected Works of Nana Asma'u. Jean Boyd and Beverly B. Mack, eds. East Lansing, Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 1997.

- Omipidan Teslim "Usman Dan Fodio (1754–1817)", OldNaija

- Mervyn Hiskett. The Sword of Truth: The Life and Times of the Shehu Usuman Dan Fodio. Northwestern University Press; 1973. Reprint edition (March 1994). ISBN 0-8101-1115-2

- Ibraheem Sulaiman. The Islamic State and the Challenge of History: Ideals, Policies, and Operation of the Sokoto Caliphate. Mansell (1987). ISBN 0-7201-1857-3

- Ibraheem Sulaiman. A Revolution in History: The Jihad of Usman dan Fodio.

- Isam Ghanem. "The Causes and Motives of the Jihad in Northern Nigeria". in Man, New Series, Vol. 10, No. 4 (December 1975), pp. 623–624

- Usman Muhammad Bugaje. The Tradition of Tajdeed in West Africa: An Overview[1] International Seminar on Intellectual Tradition in the Sokoto Caliphate & Borno. Center for Islamic Studies, University of Sokoto (June 1987)

- Usman Muhammad Bugaje. "The Contents, Methods and Impact of Shehu Usman Dan Fodio's Teachings (1774–1804)"[2]

- Usman Muhammad Bugaje. The Jihad of Shaykh Usman Dan Fodio and its Impact Beyond the Sokoto Caliphate.[3] A Paper read at a Symposium in Honour of Shaykh Usman Dan Fodio at International University of Africa, Khartoum, Sudan, from 19 to 21 November 1995.

- Usman Muhammad Bugaje. Shaykh Uthman Ibn Fodio and the Revival of Islam in Hausaland,[4] (1996).

- Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Nigeria: A Country Study.[5] Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1991.

- B. G. Martin. Muslim Brotherhoods in Nineteenth-Century Africa. 1978.

- Jean Boyd. The Caliph's Sister, Nana Asma'u, 1793–1865: Teacher, Poet and Islamic Leader.

- Lapidus, Ira M. A History of Islamic Societies. 3rd edn. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2014. pp. 469–472.

- Nikki R. Keddie. "The Revolt of Islam, 1700 to 1993: Comparative Considerations & Relations to Imperialism", in Comparative Studies in Society & History, Vol. 36, No. 3 (July 1994), pp. 463–487

- R. A. Adeleye. Power and Diplomacy in Northern Nigeria 1804–1906'. 1972.

- Hugh A. S. Johnston. Fulani Empire of Sokoto. Oxford: 1967. ISBN 0-19-215428-1.

- S. J. Hogben and A. H. M. Kirk-Greene, The Emirates of Northern Nigeria, Oxford: 1966.

- J. S. Trimgham, Islam in West Africa, Oxford, 1959.

- 'Umar al-Nagar. "The Asanid of Shehu Dan Fodio: How Far are they a Contribution to his Biography?", Sudanic Africa, Volume 13, 2002 (pp. 101–110).

- Paul E. Lovejoy. Transformations in Slavery – A History of Slavery in Africa. No 36 in the African Studies series, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-78430-1

- Paul E. Lovejoy. "Fugitive Slaves: Resistance to Slavery in the Sokoto Caliphate", In Resistance: Studies in African, Caribbean, & Afro-American History. University of Massachusetts. (1986).

- Paul E. Lovejoy, Mariza C. Soares (eds). Muslim Encounters With Slavery in Brazil. Markus Wiener Pub (2007) ISBN 1-55876-378-3

- M. A. Al-Hajj, "The Writings of Shehu Uthman Dan Fodio", Kano Studies, Nigeria (1), 2(1974/77).

- David Robinson. "Revolutions in the Western Sudan," in Levtzion, Nehemia and Randall L. Pouwels (eds). The History of Islam in Africa. Oxford: James Currey Ltd, 2000.

- Bunza[6]

- Adam, Abba Idris., "Re-inventing Islamic Civilization in the Sudanic Belt: The Role of Sheikh Usman Dan Fodio." Journal of Modern Education Review 4.6 (2014): 457–465. online

- Suleiman, I. The African Caliphate: The Life, Works and Teachings of Shaykh Usman Dan Fodio (1757–1817) (2009).

External links[edit]

- ^ "Usman Bugaje:THE TRADITION OF TAJDEED IN WEST AFRICA: AN OVER VIEW". Archived from the original on 21 January 2008. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 28 September 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Dr Usman Muhamad Bugaje: The Impact of usman Dan fodio's Jihad beyond the Sokoto Caliphate". Archived from the original on 21 January 2008. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- ^ "Dr Usman Muhamad Bugaje". Archived from the original on 21 January 2008. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- ^ "Nigeria Usman Dan Fodio and the Sokoto Caliphate". Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2010. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- 1754 births

- 1817 deaths

- 18th-century Nigerian people

- 19th-century Nigerian people

- 19th-century monarchs in Africa

- Arabic-language writers

- Asharis

- Fula-language writers

- Fulani warriors

- Hausa-language writers

- Muslim missionaries

- Nigerian Arabic-language poets

- Nigerian Fula people

- Nigerian philosophers

- Nigerian royalty

- Nigerian Sufi religious leaders

- Nigerian warriors

- Nigerian writers

- Nigerian people of Moroccan descent

- Self-proclaimed caliphs

- Sultans of Sokoto

- Dan Fodio family