Portal:Stars

IntroductionA star is a luminous spheroid of plasma held together by self-gravity. The nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked eye at night; their immense distances from Earth make them appear as fixed points of light. The most prominent stars have been categorised into constellations and asterisms, and many of the brightest stars have proper names. Astronomers have assembled star catalogues that identify the known stars and provide standardized stellar designations. The observable universe contains an estimated 1022 to 1024 stars. Only about 4,000 of these stars are visible to the naked eye—all within the Milky Way galaxy. A star's life begins with the gravitational collapse of a gaseous nebula of material largely comprising hydrogen, helium, and trace heavier elements. Its total mass mainly determines its evolution and eventual fate. A star shines for most of its active life due to the thermonuclear fusion of hydrogen into helium in its core. This process releases energy that traverses the star's interior and radiates into outer space. At the end of a star's lifetime as a fusor, its core becomes a stellar remnant: a white dwarf, a neutron star, or—if it is sufficiently massive—a black hole. Stellar nucleosynthesis in stars or their remnants creates almost all naturally occurring chemical elements heavier than lithium. Stellar mass loss or supernova explosions return chemically enriched material to the interstellar medium. These elements are then recycled into new stars. Astronomers can determine stellar properties—including mass, age, metallicity (chemical composition), variability, distance, and motion through space—by carrying out observations of a star's apparent brightness, spectrum, and changes in its position in the sky over time. Stars can form orbital systems with other astronomical objects, as in planetary systems and star systems with two or more stars. When two such stars orbit closely, their gravitational interaction can significantly impact their evolution. Stars can form part of a much larger gravitationally bound structure, such as a star cluster or a galaxy. (Full article...) Selected star - Photo credit: NASA and ESA

Sirius is the brightest star in the night sky. With a visual apparent magnitude of −1.46, it is almost twice as bright as Canopus, the next brightest star. The name "Sirius" is derived from the Ancient Greek Seirios ("scorcher"), possibly because the star's appearance was associated with summer. The star has the Bayer designation α Canis Majoris (α CMa, or Alpha Canis Majoris). What the naked eye perceives as a single star is actually a binary star system, consisting of a white main sequence star of spectral type A1V, termed Sirius A, and a faint white dwarf companion of spectral type DA2, termed Sirius B. Sirius appears bright due to both its intrinsic luminosity and its closeness to the Earth. At a distance of 2.6 parsecs(8.6 ly), the Sirius system is one of our near neighbors. Sirius A is about twice as massive as the Sun and has an absolute visual magnitude of 1.42. It is 25 times more luminous than the Sun but has a significantly lower luminosity than other bright stars such as Canopus or Rigel. The system is between 200 and 300 million years old. It was originally composed of two bright bluish stars. The more massive of these, Sirius B, consumed its resources and became a red giant before shedding its outer layers and collapsing into its current state as a white dwarf around 120 million years ago. Selected article - Photo credit: User:Mysid and User:Jm smits

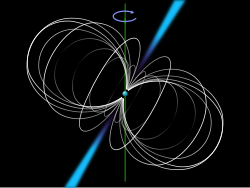

Pulsars are highly magnetized, rotating neutron stars that emit a beam of electromagnetic radiation. The observed periods of their pulses range from 1.4 milliseconds to 8.5 seconds. The radiation can only be observed when the beam of emission is pointing towards the Earth. This is called the lighthouse effect and gives rise to the pulsed nature that gives pulsars their name. Because neutron stars are very dense objects, the rotation period and thus the interval between observed pulses is very regular. For some pulsars, the regularity of pulsation is as precise as an atomic clock. A few pulsars are known to have planets orbiting them, such as PSR B1257+12. Werner Becker of the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics said in 2006, "The theory of how pulsars emit their radiation is still in its infancy, even after nearly forty years of work. The events leading to the formation of a pulsar begin when the core of a massive star is compressed during a supernova, which collapses into a neutron star. The neutron star retains most of its angular momentum, and since it has only a tiny fraction of its progenitor's radius (and therefore its moment of inertia is sharply reduced), it is formed with very high rotation speed. A beam of radiation is emitted along the magnetic axis of the pulsar, which spins along with the rotation of the neutron star. The magnetic axis of the pulsar determines the direction of the electromagnetic beam, with the magnetic axis not necessarily being the same as its rotational axis. This misalignment causes the beam to be seen once for every rotation of the neutron star, which leads to the "pulsed" nature of its appearance. The beam originates from the rotational energy of the neutron star, which generates an electrical field from the movement of the very strong magnetic field, resulting in the acceleration of protons and electrons on the star surface and the creation of an electromagnetic beam emanating from the poles of the magnetic field. This rotation slows down over time as electromagnetic power is emitted. When a pulsar's spin period slows down sufficiently, the radio pulsar mechanism is believed to turn off (the so-called "death line"). As this seems to take place after ~10-100 million years, but neutron stars have been formed throughout the ~13.6 billion year age of the universe, more than 99% of neutron stars are thought to no longer be pulsars. To date, the slowest observed pulsar has a period of 8 seconds. Selected image - Photo credit: NASA/TRACE

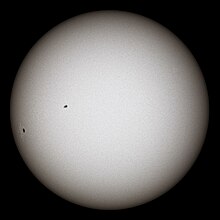

Sunspots are temporary phenomena on the surface of the Sun (the photosphere) that appear visibly as dark spots compared to surrounding regions. They are caused by intense magnetic activity, which inhibits convection, forming areas of reduced surface temperature. Although they are at temperatures of roughly 3,000–4,500 K, the contrast with the surrounding material at about 5,780 K leaves them clearly visible as dark spots, as the intensity of a heated black body (closely approximated by the photosphere) is a function of T (temperature) to the fourth power. If the sunspot were isolated from the surrounding photosphere it would be brighter than an electric arc. Sunspots expand and contract as they move across the surface of the sun and can be as large as 80,000 km (50,000 miles) in diameter, making the larger ones visible from Earth without the aid of a telescope. Did you know?

SubcategoriesTo display all subcategories click on the ►

Selected biography - Photo credit: Unknown artist, uploaded by User:ArtMechanic

Johannes Kepler (/ˈkɛplər/; German: [joˈhanəs ˈkɛplɐ, -nɛs -] ; 27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best known for his laws of planetary motion, and his books Astronomia nova, Harmonice Mundi, and Epitome Astronomiae Copernicanae, influencing among others Isaac Newton, providing one of the foundations for his theory of universal gravitation. The variety and impact of his work made Kepler one of the founders and fathers of modern astronomy, the scientific method, natural and modern science. He has been described as the "father of science fiction" for his novel Somnium. Kepler was a mathematics teacher at a seminary school in Graz, where he became an associate of Prince Hans Ulrich von Eggenberg. Later he became an assistant to the astronomer Tycho Brahe in Prague, and eventually the imperial mathematician to Emperor Rudolf II and his two successors Matthias and Ferdinand II. He also taught mathematics in Linz, and was an adviser to General Wallenstein. Additionally, he did fundamental work in the field of optics, being named the father of modern optics, in particular for his Astronomiae pars optica. He also invented an improved version of the refracting telescope, the Keplerian telescope, which became the foundation of the modern refracting telescope, while also improving on the telescope design by Galileo Galilei, who mentioned Kepler's discoveries in his work. Kepler lived in an era when there was no clear distinction between astronomy and astrology, but there was a strong division between astronomy (a branch of mathematics within the liberal arts) and physics (a branch of natural philosophy). Kepler also incorporated religious arguments and reasoning into his work, motivated by the religious conviction and belief that God had created the world according to an intelligible plan that is accessible through the natural light of reason. Kepler described his new astronomy as "celestial physics", as "an excursion into Aristotle's Metaphysics", and as "a supplement to Aristotle's On the Heavens", transforming the ancient tradition of physical cosmology by treating astronomy as part of a universal mathematical physics. (Full article...) TopicsThings to do

Related portalsAssociated WikimediaThe following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

Discover Wikipedia using portals |